The difference between a strong piece of animation and a lifeless one can be as simple as a line. This line is called the line of action, and it's essential to all dynamic scenes.

In

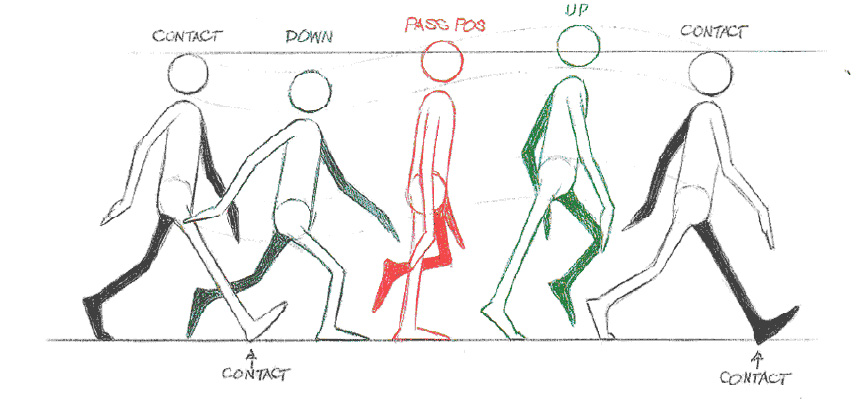

The Animator's Survival Kit by Richard Williams, this skill is described as the use of weight.

Williams writes, "...in picking up something heavy, the whole body will help" (262). In the images below, the main line that is preforming the action is highlighted in red.

In order to practice finding the line of action in various forms of media and see the dramatic effect it has, I put together some examples:

In the first example, the two superheroes from the Marvel movie Captain America: Civil War (Joe Russo, 2016) are in very dynamic poses. This is because they both have very strongly recognizable lines of action, as highlighted in red. The actions they are about to take appear much more powerful because of this as well.

In the second example, from the movie Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983) Luke and Darth Vader are facing off. Take notice of how their poses contrast each other: Luke looks as if he's exerting himself completely, while Darth Vader doesn't seem to be applying himself as fully. The reason for these distinct poses is the line of action, which is again highlighted in red. Luke's line is curved, while Vader's line is fairly straight up and down.

The Third example is from the 2017 film Wonder Woman, directed by Patty Jenkins. The woman in the air with a bow is a perfect example of a strong line of action. Her pose in the air is dramatic and dynamic, and the line of action is incredibly clear to see.

My final question is this: how is the line of action applied to other forms of media other than animations and movies?